The completion of the Fansipan Cable Project meant the world to all of the workers, engineers, and specialists, many of whom spent over 800 consecutive days in a mountainous wilderness to construct a world record-setting funicular structure, dealing with extreme conditions and working in an area with a rugged terrain and complex geology. It took much more than collective efforts. It came down to grim determination and a burning passion to bring this mega-project to life.

For each and every member of the team, this three-rope cable car project is the most challenging and dangerous mission they ever undertook. The construction of the cable-car system truly tested their limits of expertise, and required all of their experience, dedication, and even courage. This incredible journey demanded that these men pushed themselves beyond their physical and mental limits so they could conquer what often seemed like an insurmountable challenge. In the process, everyone felt like they were setting some ‘personal world records’ or experiencing life-defining moments.

A step away from death

Autumn 2015...

When autumn arrived in 2015, the project had moved to a crucial stage. The team had to perform the tricky task of pulling huge track cables across the towers. The cables were of course the critical links in the Fansipan cable car system. Nguyen Xuan Hau and his fellow constructors were racing against time to meet the deadline. One small mistake could lead to disaster.

When autumn arrived in 2015, the project had moved to a crucial stage. The team had to perform the tricky task of pulling huge track cables across the towers. The cables were of course the critical links in the Fansipan cable car system. Nguyen Xuan Hau and his fellow constructors were racing against time to meet the deadline. One small mistake could lead to disaster.

Needless to say, it was a technical headache. There weren’t just dangers in the present sense. They were required to ensure the safety of the cable car for the long-term future. Soon, the passenger cars would be attached to the cables and ferrying visitors up and down the mountaintop.

“The task required us to make sure every single thing is in place along the whole route. We cannot miss any small technical details. We had to go along the route and check everything with our own eyes,” said Nguyen Van Hau of his experience when he faced death at close range while on the job.

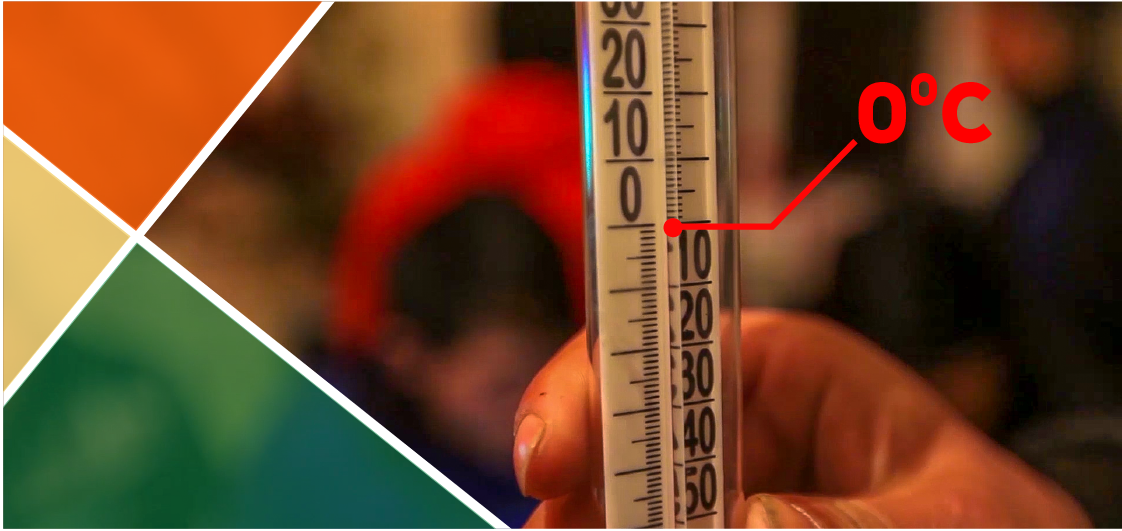

One morning, Hau checked his safety gears one last time before he headed out for the job. That day he had to climb high mountains along the length of the guiding ropes that would connect tower T1 to T2. It was still early when he left the camp. Dewdrops covering sleeping tents' roofs twinkled as it reflects sunlight. The sun was struggling to break gathering clouds under the wind. It’s the kind of scenery he enjoys. He took quicks photo of it for his memory before embarking on a perilous mountain, walking a long distance and climbing up to the height of 1.800 meters above sea level.

One morning, Hau checked the safety gears one last time before he headed out for the job. That day he had to climb up the mountain along the length of the guiding ropes that would connect tower T1 to T2. It was still early when he left the camp. Dewdrops covering sleeping tents' roofs twinkled in the sunlight. The sun was struggling to break through gathering clouds under the wind. It’s the kind of scenery Hau loved to see in the mountains. He took a quick photo of it before embarking on a perilous mountain, walking a long distance and climbing up to a height of 1,800 meters above sea level..

The climbing became more difficult and dangerous as he got closer to tower T2. One steep slope only led to another steep slope. He looked up at the high mountains that almost seemed to go straight up to the sky. The thick jungle also made every step more perilous. It became more exhausting as he walked on. He could hear the deep breaths of his colleagues, who were also struggling. But his team could not take a break. That would slow down the whole technical operation that comprised of many different teams. Hau’s team had to follow the 12-mm guiding cable that was being hauled and pulled up the mountain. It was like a giant tug of war to stop the cable from sagging into the forest. They also had to make sure the electrical lines did not create any technical problems. But the path under his feet was getting narrower, making it harder for him to see where his next would land.

When Hau was about 500 meters away from his destined point, he found himself walking between a high mountain wall on one side and a deep ravine on the other. Holding a walkie-talkie in his hand, Hau tried to move away from the edge of the ravine. If he were to slip, he realised, he would pay for the mistake with his life.

And then, Hau lost his balance…

The next thing he knew, he falling, then rolling down a sloping wall into the ravine. He heard screams and calls from his colleagues as he plummeted. He could also hear rocks tumbling down. Bushes and tree branches bashed and scratched his face. He opened his eyes but could see only darkness.

“It happened so suddenly and so fast, I did not have any time to think. I was just trying to stretch out my hands to grab onto something. Anything,” said Hau, recalling a moment that he would never forget for the rest of his life.

He had plunged into the ravine and instinctively knew he had to grab something. He felt his hands were being burnt as he reached out and tried to clasp something. It was about 12 to 13 meters down that he successfully grabbed onto some birthworts along the wall of the ravine but he couldn’t hold on. He plunged a bit more but his body came to a halt, seemingly in mid-air, but actually hanging from the birthworts. He heard more falling rocks crashing down into the ravine, all the way down; the sounds could be heard echoing faintly from far below where he was.

He tried to lift his head to look up. He breathed a big sigh of relief as he could still see his colleagues who were lowering ropes down to pull him up.

“My body suffered deep cuts and many bruises. I lost my walkie-talkie but I was grateful when God spared me that day,” Hau said, smiling at the thought of his near escape.

Another battle-hardened builder Tran Dinh Hau, who hauled electric lines on this gigantic power project, also faced another near-death experience while on the job.

At a later stage of the cable car project, when it was close to the launch date, parts of 35kV electric lines providing power to the system were ruptured.

“A contractor only agreed to reconnect the lines on what they considered ‘friendly terrain’. But they were not willing to fix the broken lines between pole No.14 and No.15, so the job was left to our team,” Luat recalled.

Between poles No.14 and No.15 was some of the most rugged terrain that we had seen when getting the 35kV electric transmitting system to the top of Fansipan. Between the poles was a ravine that was more than 100 meters deep, sandwiched between near-vertical mountain walls. A group of the most battle-hardened and experienced workers with a lot of expertise in hauling lines was called in for the task. Luat and his team faced some daunting technical challenges, right before the launch of the Fansipan cable car system.

“After the long, hard efforts of our team, we were about to finish the task, when a strong headwind started to pick up,” said Luat, recalling the erratic weather in the area, saying it had commonly led to delays and added an extra element of danger to what was already a challenging job.

“After the long, hard efforts of our team, we were about to finish the task, when a strong headwind started to pick up,” said Luat, recalling the erratic weather in the area, saying it had commonly led to delays and added an extra element of danger to what was already a challenging job.

The pole was in the middle of a thick forest, surrounded by rugged terrain. Because of the injury, and as he was losing too much blood, Luat could not walk on his own. His colleagues carried him out of the area on an improvised stretcher made out of a blanket and branches of wood. They were worried Luat was on the verge of sinking into a coma as they carried him down the mountain to seek medical care.

“The journey through the terrain was so treacherous. At certain parts, my teammates could not carry me, they just had to pull me along. About three hours later when we reached Ton base camp, I was dropping in and out of consciousness. Worried I would slip into a coma, they slapped me really hard to revive me,” Luat recalled.

The episode left Luat with a scar on his forehead. He also required stitches for wounds on his arms and legs. But the incident did not deter him from returning to work.

“I was not scared at all. I had overcome much more dangerous challenges. That was nothing at all,” he said.

Remembering that there was some skepticism regarding the Fansipan cable car project, due to what seemed like insurmountable challenges, it’s clear from these stories of sacrifice and brave dedication that it was passionate builders such as Tran Dinh Luat and Nguyen Xuan Hau who made the operation of the funicular project achievable. The completion of the structure, once considered a wild dream, would eventually become a reality, setting world records in the process. Many of the workers who worked on the project are rightly proud of their achievements. The project depended on their personal sacrifice and commitment. They spent over 800 days in the wilderness of the Hoang Lien mountains, giving their all to make this dream a reality.

Vo Hoai Quoc is one such worker who looks back with great pride on the record-breaking cable car system.

“The Fansipan cable car system was recognised for setting two world records on the day of its launch,” the engineer said. We joked that we had also set our own personal records, such as, ‘longest project we had ever worked on’, or ‘the most remote construction we had ever built’. We’d probably lived on top of the famous Fansipan longer than anyone! We also became the faster and luckiest climbers to reach the Fansipan summit.”

Vo Hoai Quoc, while trying to help an injured colleague receive medical care, also set a ‘record’ for the fastest ever trek through one mountainous area. It took them only three hours to traverse a distance of 12-km through rugged terrain — it would usually take eight hours for the average local mountain climber to have made this trek.

“At 5.30 in the morning, it was still dark outside. Mr Minh walked out of the tent to prepare the gears. He suddenly rushed back to the tent in distress,” Vo Hoai Quoc wrote in a memoir about his experience working on the Fansipan cable car project. “Quoc, can you help take a look for me —what kind of snake is this? I feel so numb here!” said Minh, pointing to four marks of a snake bite above his elbow. The snake must have been so big. What a bite it was!”

After making a garrotte and wrapping it tightly around the bitten area, Quoc hastily grabbed some luggage. Along with another teammate, A Su, Quoc hurried to take Mr Minh to find medical care. What happened next would set another ‘record’ for those who built the Fansipan cable car.

“Mr Minh and I followed a mountain trek as we rushed to a village. We ran as fast as we could. Sharp thorns of jungle bushes slowed us down. It cut into our feet, our legs. Mr Minh fought back his pain, trying to run as fast as possible to seek treatment in time. I was running behind him, followed by A Su, who was trying also to catch his breath.”

“The mountain trek was blocked by fallen trees or boulders in many parts. Some other parts were covered in moss and it was very slippery. But we could not slow down. We could not afford any minute of slowing down as Mr Minh was in need of urgent medical care,” Quoc wrote in the memoir.

As he ran, Quoc also tried to make calls on his mobile phone to seek help. When the men made it out to the other side of the forest, there was a car waiting to take Mr Minh to a medical facility. When he saw the car waiting, Quoc wept with relief and hope. After the car drove out of his sight with Mr Minh in it, a question came to Quoc’s mind: How on earth had they made it through the forest so fast, running up such steep slopes? With the adrenalin pumping through their bodies, they hadn’t even noticed the superhuman efforts they had made. It was only later when he could recall this epic run through the wilderness of Hoang Lien mountain range.

“We ran past the area of tower T3. Mr Minh’s arm was clearly swelling badly around the snakebite. I had to tear up his shirt to make him feel less uncomfortable around the wound. His face turned pale. But he made a huge effort to soldier on through a dense part of the forest. It would have been very easy to get lost here. If we’d lost directions there, Mr Minh would have had to pay with his life. We just kept running.”

We were filthy dirty and exhausted when we reached the 1,800m point of elevation. We could see the venom had taken its toll on Mr Minh as his face had grown much paler. We rushed over to him and carried him. He started to breath very heavily. It had become a really perilous situation.

- Uncle Minh you can do it! We are almost there!

A Su and I just helped him and carried him for the rest of the journey.

At around nine in the morning, the car that had been waiting in Ton base camp was now rushing toward Sa Pa hospital. By then, Vo Hoai Quoc and his teammates had just finished the long mountain trek in less than three hours, a record of its kind, and one that doctors say helped save Mr. Minh’s life. He was discharged from the hospital 14 days later after making a full recovery.

“I did not realise the significance and the scale of the project until all of our work was completed. We took great pride in our contribution to it. It helped us set a few records for ourselves! It all contributed to a miracle…”

Epilogue

On those last days of 2018, we tried to revisit some of the places where Vo Hoai Quoc, Nguyen Xuan Hau and many other of the builders had experienced so many of these life-defining moments. But deep in the wilderness of the Hoang Lien mountain range, there were only faint reminders of their most perilous journeys.

The tree trunk that served as a bridge crossing the ravine had collapsed. The rope that provided much need safety for the workers had disappeared. Much of the evidence of the builders’ lives in the wild could not be seen. Bushes, trees, shrubbery and grown over many of the traces.

Tran Dinh Luat, the technician paused to reflect every time he found any faint traces of the 800 days and nights he and his colleagues spent here.

“We will leave this place some day, but we have all left parts of ourselves here — our tears, our sweat, and even our blood — it is all belongs to the Hoang Lien mountains now.”

Above our heads, one of the cabins ran along this world-record setting cable car system, humming high above the forest and zipping across the blue skies of Sa Pa to the roof of Indochina, and while standing with the engineers and workers, listening to their incredible stories, we were reminded that the Fansipan Cable Car is truly a man-made miracle.

-

Album: Fansipan cable car - Works of records

Album: Fansipan cable car - Works of records

-

Album: Fansipan Cable Car - A World Record Breaking Project

Album: Fansipan Cable Car - A World Record Breaking Project

-

Article: 800 Days of carring stones up a moutain

Article: 800 Days of carring stones up a moutain

-

Article: Bringing electricity to ‘the roof of Indochina’

Article: Bringing electricity to ‘the roof of Indochina’

-

Article: Taking cable-car engineering to new heights

Article: Taking cable-car engineering to new heights

-

Article: The most perilous moments

Article: The most perilous moments

-

Album: The Tarzans of Hoang Lien Forest

Album: The Tarzans of Hoang Lien Forest

-

Album: The sky high temples of Fansipan

Album: The sky high temples of Fansipan

-

Album: A flag-raising ceremony on Fansipan

Album: A flag-raising ceremony on Fansipan

-

Album: Out in the woods

Album: Out in the woods

Documentary Fansipan cable car

Documentary Fansipan cable car