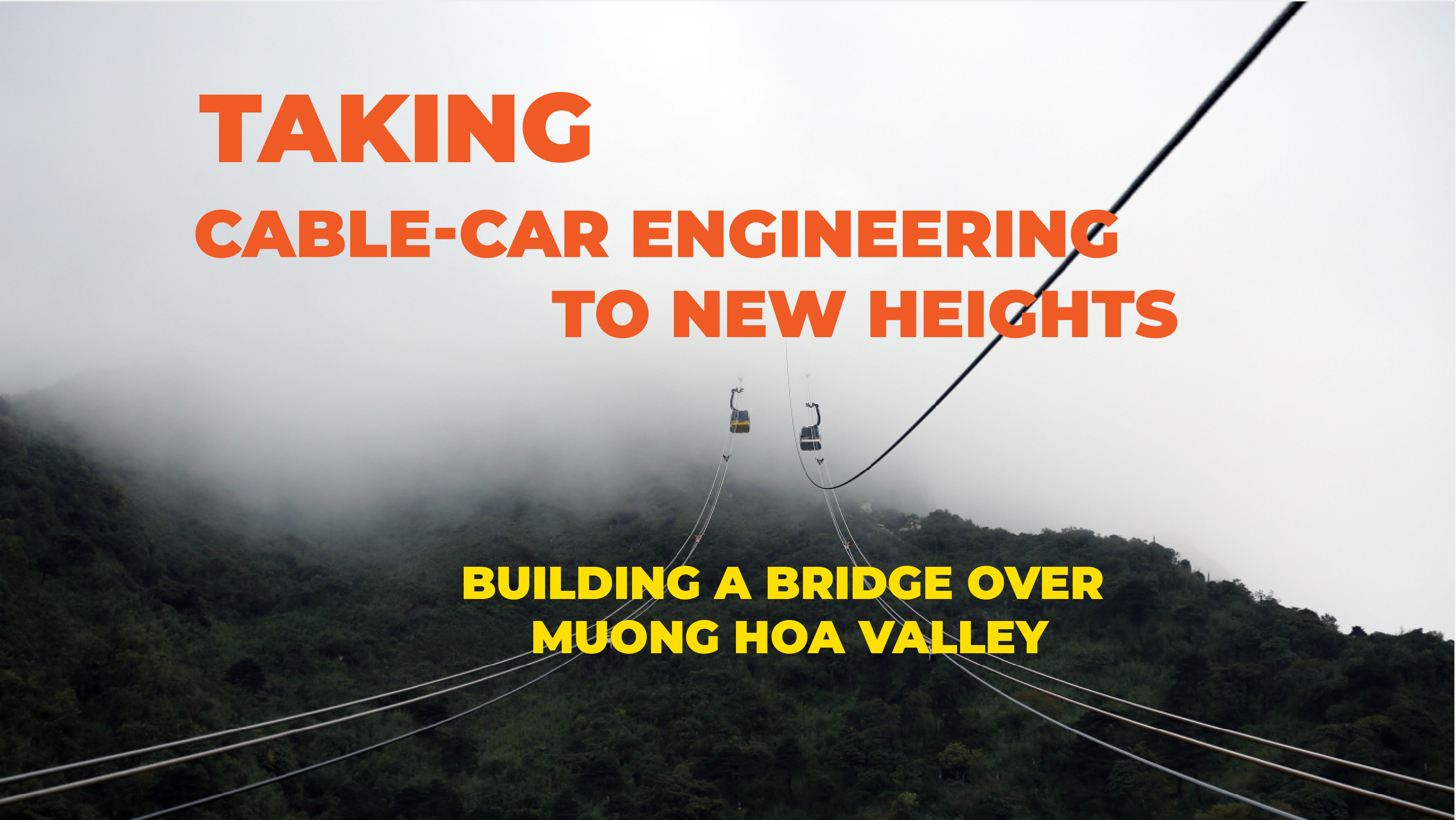

The construction of the Fansipan cable car system presented many monumental technical challenges. Chief among them was the installation of the three-cable system onto the towers that support the structure. The Doppelmayr/Garaventa group— the world's leading manufacturer of ropeways, cable cars and ski lifts — admitted it was one of the most difficult projects they had ever attempted.

One Flycam (worth tens of thousands of dollars) being used to ferry and haul the guiding cable line was lost forever in a ravine due to technical problems.

The extreme terrain and complex geology of Hoang Lien mountain range also initially confounded the contractor. To lift the three-cable system onto the towers would require utterly unique solutions with a high level of technical complexity.

The Initial Cable System

The three-steel cable system carrying passengers today was not the first cable line connecting Sapa to the summit of Fansipan. The first cable line was installed back in 2015. Named the Logistics System Cable (LSC), this was the cable that first linked the towers. Essentially it’s the backbone that defined the future success of the project.

In July 2014, eight months into the project, construction was falling far behind schedule. Ferrying materials and structures through rugged terrains to designated positions perched up a mountain was a mammoth task. Manual labour could only do so much. The engineers decided to build a cable system that would ferry materials, equipment, and pieces of the structure to designated locations, to put them in a position to install the actual cable car system.

“At that time, the construction of a transporting cable system, or the LCS was the only option we had. Without it, the whole project would fail,” said Phan Tat Thang, the Deputy Engineering Director at Fansipan Sapa Cable Car Tourism and Services, who oversaw the project.

A group of top cable car specialists from Doppelmayr - Garaventa were called in. To come up with technical strategies and solutions, they arrived in Vietnam from Switzerland to study the construction site’s terrain, geography and other technical conditions.

At the same time, Vietnam’s top architecture engineer Pham Duc Hung, who designed the Ba Na cable car system, was also summoned. It took the specialists numerous survey trips to collect enough data and decide they needed to build a transport cable system, if they wanted to move the project ahead.

The Doppelmayr Garaventa specialists originally suggested installing the transport cable system with a helicopter or hot-air balloon, which they had done for many projects. But the heavy and erratic headwinds that came out of O Quy Ho pass across the mountains of Hoang Lien Range spelled too much danger for a helicopter or hot-air balloon. As they could not cutting down the forest (the investor was adamant that the forest would not be damaged) they were left with only one single solution: man power.

Big groups of workers toiled day in and day out. They bent, they hoisted, they hauled. Piece by piece. Inch by inch. They carried large pieces of the structure and equipment through the forest, across streams and up the mountain.

Reto Sigrist, an engineer at Doppelmayr - Garaventa was stunned when he saw the giant man-powered operation in progress. “It was being done here like nowhere else before,” he said.

As impressive as it was, there was one critical resource they could not waste. Time. Another engineer from Doppelmayr - Garaventa warned that if it were done ‘by hand’ it would take five years or more to implement the project.

Nguyen Xuan Hau was among those who worked on the initial cable line. The first technical task was installing guiding ropes. Different group of haulers had to pull different segments of the guiding ropes, which were 6mm in diameter. All of the segments were then connected into one single guiding rope. The guiding rope would be later hung up by attaching its ends onto towers with the support of winches.

“It might sound very simple, but lining the cable with hundreds of meters in length across the Hoang Lien mountain range was a daunting task,” said Tam, another worker who participated in building the ferrying cable system.

“We could not cut the trees down, so we had to haul the cable manually by pulling one end of the cable line and walking along the length of all the distance we wanted to link up. We had to climb up into trees to hoist the cables,” said Tam, who feared he would fall from the tree tops to the ground. The rugged terrain, especially the steep mountainous slopes, and extreme weather conditions made this an especially tough job.

The toughest section was between Tower 3 and the arrival terminal. In between there was a deep ravine. They had to figure out how they could run the guiding rope across the mouth of the ravine, which was hundreds of meters deep. That terrain also invites a strong sidewind, which presented another challenge.

Long after the project was completed, mentioning the words ‘Tower 3’ still sent shivers down the spine of Tam. He recalled how the wind blew incessantly in this area. “It seemed like the wind got stuck there, swirling around between the mountains,” Tam said.

“It made the job of linking the guiding rope between the towers especially dangerous. This part was the hardest stretch for the whole cable line system. We had to climb down into the ravine, walk across its width, and then climb up to the top again, just to get the guiding rope across. Inside the ravine, the mountain ‘slope’ is nearly a vertical, so it was very hard or just impossible to climb. We had to hire local H’mong to help us make and hang ladders so that we could get to the bottom of the ravine.”

It took one whole month for the team to successfully hang the 6mm guiding rope across that gap between high mountains. The the first ever-unbroken link between Sapa and the roof of Indochina had been established.

After that, the thicker guiding ropes (12,18 and 42mm thick) were respectively connected and hauled up by winches. The LCS was operational by January 2015. Tam and Hau, and many of the other workers who had made it all possible, jumped for joy when they saw the LCS running. This was a huge moment, one that would make the impossible dream of building the Fansipan cable car project seem achievable. “There wasn’t any official tower at that time, but wherever we were gathered, we really cheered out loud in celebration. With the LCS running, we could all suddenly imagine a day when the whole cable car project was finished. We had not been that optimistic for a long period of time,” Nguyen Xuan Hau said.

Establishing links to the roof of Indochina

The operation of the logistics cable system (LCS) provided a big lift for the cable car project. Tonnes upon tonnes of heavy equipment, steel structures as well as materials were now being ferried to the six construction sites up in the mountains. At the same time, the 35kV electric line had also been completed, making the construction speed accelerate rapidly. It only took three more months to erect the four main steel pillars from T1 to T4. The "crazy guys" of Hoang Lien forest were now just a short distance from completing a transport link from Sapa to the summit of Fansipan.

But first, the main cable had to be hauled to the top. To do so, 32 Doppelmayr - Garaventa experts, seven interpreters and thousands of Vietnamese workers and engineers were mobilised, spread out over the departure station, the four pillars and the arrival station. Twelve temporary poles to hold the cable were also quickly built along the route. The radios worked constantly. An unprecedented atmosphere of excitement encompassed everything.

The first main task was to haul the first guiding rope with a diameter of 12mm through the T pillars. Meanwhile, a team had to walk closely underneath to ensure the wire kept it above the trees.

“As the LCS line came close to each T pillar, the workers only had to lift the guiding rope and tie it to each pillar’s top,” said Nguyen Xuan Hau to explain how they managed it.

The operation was going smoothly, but once more, the wind blew through the ravine causing huge problems, this time for the experts from Switzerland.

In order to reduce time, and conserve energy, Doppelmayr - Garaventa had proposed using an eight-wing Flycam to ferry the guiding rope over the ravine. The Flycam, worth more than VNĐ1 billion when purchased, was the most modern type of Flycam in mid 2015. This device had great stability in strong winds, and could even be located by satellite. That morning, hundreds of Vietnamese workers were looking at the Flycam slowly rising above the forest. For most of them, it was the first time they saw a machine that could fly and ferry a cable wire at the same time. There were strong gusts of wind blowing across the ravine but they could see the eight-wing Flycam still buzzing forward: 10 meters. 20 meters. 30 meters... The Flycam flew on. The foreign experts, watching through binoculars, were relieved as the device gradually shifted its trajectory in the direction of the last pillar.

But at this very moment, the monitoring screen flashed and a warning sign sounded. Something was wrong. The turbulence of the wind was obviously effecting the Flycam. The warning sound went on until, just a few seconds later, on the screen, the blue dot, which indicated the Flycam, disappeared. The plan had failed with the destination only a short distance away. So near, yet so far. Once again, the LCS “mother cable” had to ferry the “child cable” into position. Dozens of workers now had to climb down into the ravine and carry the cable back up to the other side.

On July 2, 2015, the first guiding cable wire was put into place. Subsequently, more wires were connected. After another five efforts at pulling the guiding rope, the 135-tonne main cable was finally pulled up to the Hoang Lien construction site.

Two foreign experts and three technicians were assigned to walk along the route to supervise the connecting points of the guiding cable wire and the main cable wire from the departure station to the arrival station. “It was the most stressful time I've ever experienced. As I followed the foreign experts along the route to track the connection points, I felt a burning sensation in the pit of my stomach,” Hau recalled.

Due to the strict technical requirements for the main cable, the monitoring team had to ensure that the cable was not touching the ground or the electricity wire. At the same time, it was necessary to keep the wire from over-stretching, to avoid the collapse of the pillars, or the wire breaking.

The young interpreter and three experts said their legs felt numb after all the walking.

“It was so tense. Because with just a tiny mistake, the efforts of hundreds and hundreds of people would go to waste,” said Hau.

10 meters. 20 meters. 30 meters ... The helicopter carrying the guilding rope was still flying. The foreign experts, with their hands holding binoculars, were relieved as their device gradually shifted its trajectory towards the end of the last pillar..Reto Sigrist was the one who knew the feeling better than any one. During the walk, he fell down and suffered a gash on his leg that required six stitches. Nguyen Xuan Hau also fell and almost slipped down into the ravine but he managed to reach out and grab a tree vine and climb back to safety.

"Probably because God felt sorry for me for all of the efforts I had made," the young man said of the incident with a wry smile.

With the utmost efforts from all, on August 23, the first 135-ton cable reached Fansipan Station, which caused great excitement but there were two more to go. Finally, in December 2015, the last cable finally reached its destination — the first three-wire cable system in Vietnam, and indeed all of Asia, had been established.

“When the last cable was put into position, we were in the town of Sa Pa. Twenty foreign experts rushed down the street. They would hug anyone they met and told them about the success. The Vietnamese workers along the route cheered and many burst into tears,” said Phan Tat Thang. “They had all suffered through the labour, but finally, their ‘child’ was born. Later on, I asked the foreign experts if they would join us to work on another Fansipan cable car, they shook their heads and said they would never do any similar cable routes.”

At the time it was completed, the cable car project immediately established a series of milestones. The service holds two Guinness World Records: the longest non-stop three-rope cable car in the world, spanning 6.3km, and the greatest elevation difference (1,410m) for a non-stop three-rope cable car.

More than any one, the ‘Tarzan electricians’ and the ‘crazy guys’, all of the workers, and the engineers, who spent more than 800 days in the forest on the mountainside toiling on this project, are the ones who can be absolutely proud of these records.

-

Album: Fansipan Cable Car - A World Record Breaking Project

Album: Fansipan Cable Car - A World Record Breaking Project

-

Article: 800 Days of carring stones up a moutain

Article: 800 Days of carring stones up a moutain

-

Article: Bringing electricity to ‘the roof of Indochina’

Article: Bringing electricity to ‘the roof of Indochina’

-

Article: Taking cable-car engineering to new heights

Article: Taking cable-car engineering to new heights

-

Article: The most perilous moments

Article: The most perilous moments

-

Album: The Tarzans of Hoang Lien Forest

Album: The Tarzans of Hoang Lien Forest

-

Album: The sky high temples of Fansipan

Album: The sky high temples of Fansipan

-

Album: A flag-raising ceremony on Fansipan

Album: A flag-raising ceremony on Fansipan

-

Album: Out in the woods

Album: Out in the woods

Fansipan Reporting

Fansipan Reporting