During the construction of the Fansipan cable car, one of the greatest challenges was figuring out how to create a stable and long-term power supply to serve the immediate construction needs as well as normal operations later on.

To solve that problem, on November 6, 2015, a special task force was formed. Their mission? To pull a 35kV line all the way to the top of Fansipan. ven insiders wondered if it could be done. The journey to bring electricity to a height of 3,143m was like a mythical feat in their minds.

The greatest high-wire act of all time

Winter 2015.

In Sapa, and all around the mountain town, everyone knows what the O Quy Ho wind feels like. This wind takes its name from the O Quy Ho mountain pass, where it emerges. The wind can be so hot and dry that locals say it burns the landscape, dries out waterfalls and turns the grass yellow. When it swirled away from Lai Chau, and blew across the Hoang Lien mountain range in the direction of Sapa, it caused Tran Dinh Luat to shudder. The young electrical engineer was lying on a cold, mossy stone, looking up at the mountain, and wondering, “Will we ever able to reach the pillar and bring electricity to the top of the mountain?”

It was the first time Luat had followed his colleagues to the summit of Fansipan to survey the pillars and try to pull the 35kV line up the mountain. Almost immediately, Luat was left behind. He was not able to keep up with the rest of the team.

Even the optimists in the group had serious doubts about pulling 10km of electrical lines through the mountainous terrain with deep ravines and dense forest. How could the pillars be built when it was impossible to bring any machinery into the deep forest?

One day after this first trip, Tran Dinh Luat was ready to quit. “At that time, I really felt disheartened. I thought that bringing electricity up to a summit of 3,143m was just too crazy an idea,” Luat said.

He was so disillusioned that he handed in his resignation. However it was not accepted. He was convinced to stay behind and accomplish something “crazy yet meaningful for the homeland" as his workers often said to each other, tongue-in-cheek. So Luat went back up the mountain again, trekked through the forest, but he was still wondering how this 35kV line that could reach the mountaintop.

To build 33 electric poles — running from Ton base camp to Fansipan’s summit — over the following months, more than 300 workers were mobilised. They came with crowbars, pickaxes and shovels into the forest. All kinds of materials were gathered at the foot of the mountain. Hundreds of people from Hill Tribe communities — H'mong, Red Dzao, ethnic Thai — were hired to join the construction team, carrying steel and stones to the designated locations. It was another huge human-effort.

Day after day, sometimes enduring rain, and on occasion even snowfall, the workers persevered, carrying sand and gravel up the slope in the most rudimentary, painstaking way. More than 15,000 tonnes of materials passed through the deep forest in this fashion.

While the transportation of materials was difficult, the construction was even more challenging. Clearing the construction site, digging pits, pouring concrete, everything was done manually. Due to the dry season, water was extremely scarce. Workers were forced to go deeper into the forest to source water from streams to make cement and for daily use.

By early November 2015, thousands of tonnes of cement had been poured, enough to creat 33 power poles in the middle of the wilderness that is Hoang Lien forest. The workers all marvelled at the sight. “Seeing the poles go up, everyone was over the moon. We hugged each other tightly, even though our hands and faces were covered with dirt and dust,” said Nguyen Van Binh, a supervisor working on the project. In spite of the accomplishment, challenges remained. The pillars were ready. Now, how would they pull the lines up the mountain? There would be many more strenuous work days ahead for young men like Tran Dinh Luat.

The “Tarzan electricians” of Hoang Lien forest

Fansipan is the apex of the Hoang Lien mountain range, which is home to a highly complex topography with thick forest, ravines, precipitous slopes and much more besides. Pulling a power line through this terrain was never going to be easy, especially as protecting nature was an absolute priority for the investor. If they were to pull the line without cutting trees down, the workers would not be able to bring trailers or any kind of machines to support the line pulling. Once again, they would rely on simple manpower. Workers had to walk the forest trails, spreading the lines along a 16km route from Ton base camp to the top of the mountain.

“Basically, we spread light-weight 8mm diameter wires from one column to the next. After being stretched to the post, the larger 35kV wire would be tied up to these wires and pulled up. For nearby poles, which were located on a fairly smooth terrain, it was not a big deal. But for poles with ravines or gorges between them, it was really miserable for us,” said Luat.

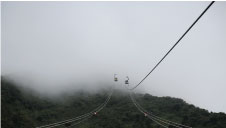

One particularly challenging location was between the 14th and 15th poles. The distance between the poles was 589m but there were also ravines and gorges to be crossed. One was more than 100m wide. Looking up at steep mountain face, all covered with mist, the workers took turns shaking their heads, wondering how could it be done. The contractor brainstormed options: could they use a hot air balloon to take the wire across the gorge? Or a crossbow to shoot the wire from one pole to another? Neither were feasible. The wind on Hoang Lien was too fierce? The ballon would unable to take off. An arrow would never reach its target. "There was only one option left for us to take: to swing down into the ravine,” said Luat recalling the moment when the decision was made.

The protective wire was released from the edge of the ravine and dropped slowly into the abyss. The electricians, using canyoning equipment, descended into the misty air of the ravine, which had a depth of over a hundred metres.

Two years later, Tran Dinh Luat still remembers exactly how he felt: “Cold and terrified.” He admits that initially he did not dare to do it. It was only after several colleagues went successfully that he was brave enough to follow. The wind was still blowing hard. Luat’s hands went numb. Even though it was cold, he was sweating all over. Only when his feet touched a thick layer of rotten leaves at the bottom of the gorge did he let out a sigh of relief.

In the end it took the team almost a month to spread more than 600m of wires across the ravine.

On September 2, 2015, after nearly a year of struggling through the forest, the special task force flicked a switch and a light on top of Fanispan went on. The ‘Tarzan electricians’ of Hoang Lien forests were euphoric. They hugged each other and shouted for joy. Some were moved to tears. In the end, one of the most insane, impossible journeys had reached its destination. They had brought electricity to the roof of Indochina.

This instantly set a new record for highest power line in Vietnam. But more than that the 35kV line running up the moment was considered the instrumental bloodline that would give life to the entire construction of Fansipan cable car. From this point, the project had turned a corner. There was now light at the end of the tunnel.

-

Album: Fansipan Cable Car - A World Record Breaking Project

Album: Fansipan Cable Car - A World Record Breaking Project

-

Article: 800 Days of carring stones up a moutain

Article: 800 Days of carring stones up a moutain

-

Article: Bringing electricity to ‘the roof of Indochina’

Article: Bringing electricity to ‘the roof of Indochina’

-

Article: Taking cable-car engineering to new heights

Article: Taking cable-car engineering to new heights

-

Article: The most perilous moments

Article: The most perilous moments

-

Album: The Tarzans of Hoang Lien Forest

Album: The Tarzans of Hoang Lien Forest

-

Album: The sky high temples of Fansipan

Album: The sky high temples of Fansipan

-

Album: A flag-raising ceremony on Fansipan

Album: A flag-raising ceremony on Fansipan

-

Album: Out in the woods

Album: Out in the woods

Fansipan Reporting

Fansipan Reporting